A conversation with the indomitable Gita Ramaswamy

Neeta Gupta talks to Gita Ramaswamy, Trustee, Hyderabad Book Trust, to know more about the Trust and the books they publish. Excerpts.

Gita Ramaswamy has worked extensively with Dalits on manual scavenging, bonded labour, agricultural wage labour, and land entitlements. She has authored The Child and The Law, Unicef, 1996; Women and The Law, Unicef 1997; co-authored The Lambadas: A Community Besieged, Unicef, 2002; co-authored Taking Charge of Our Bodies: A Health Handbook for Women, Penguin 2004;India Stinking: Manual Scavengers in Andhra Pradesh and Their Work, Navayana 2005, co-authored On Their Own: A socio-legal investigation of inter-country adoption in India, Otherwise Publications 2007, among others. After working tirelessly in the space of Telugu language publishing for more than 43 years, Gita Ramaswamy finally launched an English language imprint, Southside Books, in 2023.

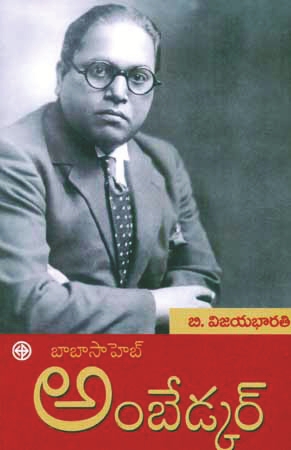

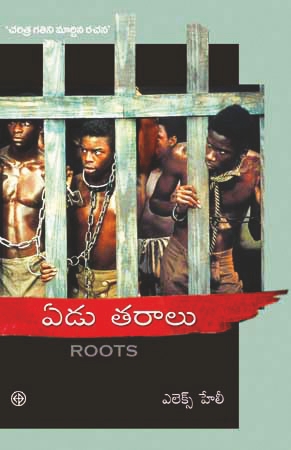

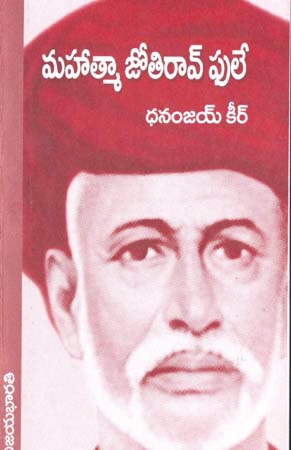

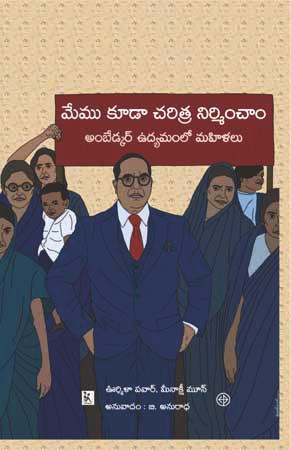

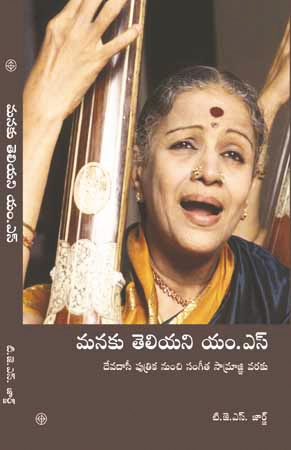

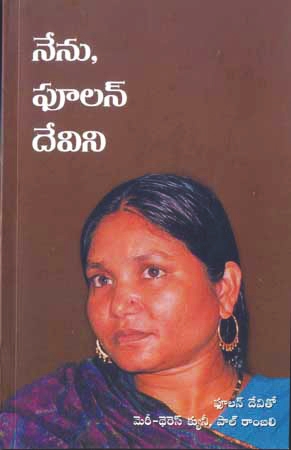

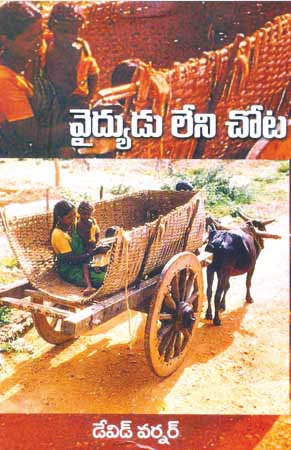

The Hyderabad Book Trust (HBT) is a not-for-profit collective that has been publishing alternative literature – the best of global and Indian literature in translation, and original commissioned literature, in Telugu, since 1980. These books have depicted the life and tribulations of marginalised sections of society, examined the Hindu epics under the lens of history and caste oppression, memorialised the lives of those who have contributed to change in society from Che Guevara, Martin Luther King, Marie Curie to Phoolan Devi, Ambedkar, Phule and Periyar. Over these 43 years, HBT has published over 420 books.

Gita Ramaswamy is the Trustee of the Hyderabad Book Trust and an prolific author. Here, she shares more about her journey.

Why did you choose publishing as a platform?

Gita: I did not choose publishing as a career, rather publishing chose me. When I returned to Hyderabad in 1980 and back to political work in my own region, the atmosphere (both about police and the radical Left) was not conducive to activist work with people. I was encouraged by my (later) mentor CK Narayan Reddy to join him in a publishing venture because he knew that I loved books. He hand-held me for nearly a year and introduced me to the world of Telugu literature. We had a great team of writers and translators to start with. Work with HBT allowed me to travel extensively in the villages and towns of the two Telugu states and meet people and readers from all sections. I could speak Telugu earlier and learnt to read and write Telugu on the job.

Gita, were you the first woman publisher in Telugu?

Gita: I don’t think there were women publishers at the time, though I should qualify the term publisher. A publisher is someone who vets and commissions originals and translations, largely from other people. Some women authors self-published their books at that time (as they do now), but no one, I think, who fit the term ’publisher.’ I did not find myself lonely. Being a woman was a tremendous asset to me. I could work hard at the pace I set for myself. I was taken seriously and appreciated more than my worth.

What is the market for translated books into Telugu?

Gita: HBT has always been more known for translations than for original works. Of late, the market for translated books in Telugu has improved, though I suspect that this is because readers are vexed with the poor quality of original works.

Translated works have been received well by Telugu readers though it is a segmented market. Dalit readers receive Dalit translations well, feminist readers take to feminist translations, Left readers buy translations of Left writers. So, while publishing translated works, we take care to ensure that there is a market for the work.

Where general readership is concerned, original works have more prestige in the Telugu literary world and authors win awards aplenty. Not so for translated works. Peculiarly, awards (even for original works) don’t necessarily result in greater sales. Though HBT translations have won 4 Sahitya Akademi awards, these awards have not generated sales. (We received awards for Yagati Chinna Rao’s Dalit’s Struggle For Identity, 2009, Sivarani Devi Premchand’s Ghar Me (Hindi), 2014, Revathi’s The Truth about me: A Hijra life story, 2019, and Bhasha Singh’s Unseen: The Truth about India’s Manual Scavengers, 2021).

The translated books that have generated the greatest sales are those whose content is appreciated by non-literary lay readers. For example, Where There is No Doctor by David Werner, Roots by Alex Haley, works by Ambedkar, Phule and Periyar – these books have sold thousands of copies more than the best original works in Telugu in the same period. Again, the works of Bama, Sarah Abubacker, Kishore Kumar Kale, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, Mahasweta Devi, Niranjana, Chingiz Aitmatov, Vaikom Mohammad Basheer, Ismat Chughtai, Richard Wright, Colson Whitehead, and others we translated have not done as well as they should have.

Publishing translations is expensive. How do you make it sustainable in your market? What kind of support, both public and private, is available for translations into Telugu? Is there any government buy back for translated works?

Gita: No support by government exists, nor do public libraries buy books that do not come with hefty bribes. Only the book reading market sustains translations. We have worked on the assumption that if one book does well (sells over 3,000 copies), it will support nine others that are not expected to do well. It has been a tough fight for HBT for over 43 years, sustained only because we have wage parity inside the organisation, goodwill among readers and book-sellers who pay us our dues. This is not to forget the hundreds of book lovers, writers and reviewers who have given us their time and energy free of cost over the years. We have not received any funds for translation or publication till we began work with Zubaan and the Tamil Nadu State Translation Board last year. For 42 years, we depended totally on the sales of books. Publishing translations in Telugu has been possible because all the stake-holders have not been compensated enough.

What distinguishes your journey in publishing translations?

Gita: I think HBT broke new ground by bringing in general political literature into Telugu. Till that time, literature was either Communist or ‘gentrified’. We brought in literature from the liberal world in history, anthropology, science, health, pedagogy and irreverent cartoons, and introduced Dalit, Adivasi and feminist voices in Telugu. People warned us that we were treading dangerous ground, the books wouldn’t sell, they were ahead of their times…but I now realise with the spate of books in Telugu in these very areas that pioneering has its rewards. We publish Dalit literature extensively – apart from publishing Ambedkar and the other greats, we have translated and published nearly every note-worthy Ph.D. thesis from Telugu Dalit scholars to encourage greater scholarship from these sections. Again, compared to other publishers in Telugu, I read widely in English and so have a distinct advantage in selecting titles and contacting writers/publishers for permissions.

What kind of voices do you showcase through your publishing house?

Gita: The voices of the marginalised – women, Adivasis, Dalits, LGBTQs, Muslims – those whose voices were rarely heard in Telugu. Apart from lay reading, we published translations and originals of PhD theses of scholars from these communities because their voices and scholarship are so important.

If there was just one story from your past/present experiences that you think hasn’t been heard enough by English-speaking readers – please do share?

Gita: I don’t know if this is a story, but this is something I did not write in my book – the devaluation of Indian language literature in India. I’ve had 43 years of publishing in Telugu (a language I am much less familiar than English – and I had offers to go into English language publishing too) and I’ve seen constant devaluation of Telugu when compared to English. The truth of this hit me only after the publication of my own memoir, Land Guns Caste Woman (Navayana 2022). Its relative success and the recognition I received after this book pained me that 43 years of donkey’s work in Indian language literature was not recognised as was a single English book.

Gita Ramaswamy has worked extensively with Dalits on manual scavenging, bonded labour, agricultural wage labour, and land entitlements. She has authored The Child and The Law, Unicef, 1996; Women and The Law, Unicef 1997; co-authored The Lambadas: A Community Besieged, Unicef, 2002; co-authored Taking Charge of Our Bodies: A Health Handbook for Women, Penguin 2004;India Stinking: Manual Scavengers in Andhra Pradesh and Their Work, Navayana 2005, co-authored On Their Own: A socio-legal investigation of inter-country adoption in India, Otherwise Publications 2007, among others.

Gita Ramaswamy has worked extensively with Dalits on manual scavenging, bonded labour, agricultural wage labour, and land entitlements. She has authored The Child and The Law, Unicef, 1996; Women and The Law, Unicef 1997; co-authored The Lambadas: A Community Besieged, Unicef, 2002; co-authored Taking Charge of Our Bodies: A Health Handbook for Women, Penguin 2004;India Stinking: Manual Scavengers in Andhra Pradesh and Their Work, Navayana 2005, co-authored On Their Own: A socio-legal investigation of inter-country adoption in India, Otherwise Publications 2007, among others.

Comments are closed.